The Spanish State Defense Lines

by Jan KuipersForts, bastions, fortified towns, defence line dikes and waterways. Almost 450 features in an area measuring 80 by 40 kilometres on both sides of the Belgian-Dutch border between Knokke and Antwerp: these are the Spanish State Defence Lines. A military raid on Terneuzen in 1583 served as the trigger: some of these elements still played a role in the Second World War. The name Staats-Spaanse Linies, as in Spanish State Defence Lines, is a modern term used. The entire network it refers to represents roughly four hundred years of history of Zeeuws-Vlaanderen, West- and East Flanders and Antwerp. In recent decades, the defence lines have been made more ‘tangible’. Museum Het Bolwerk in IJzendijke serves as a centre of knowledge.

Time span

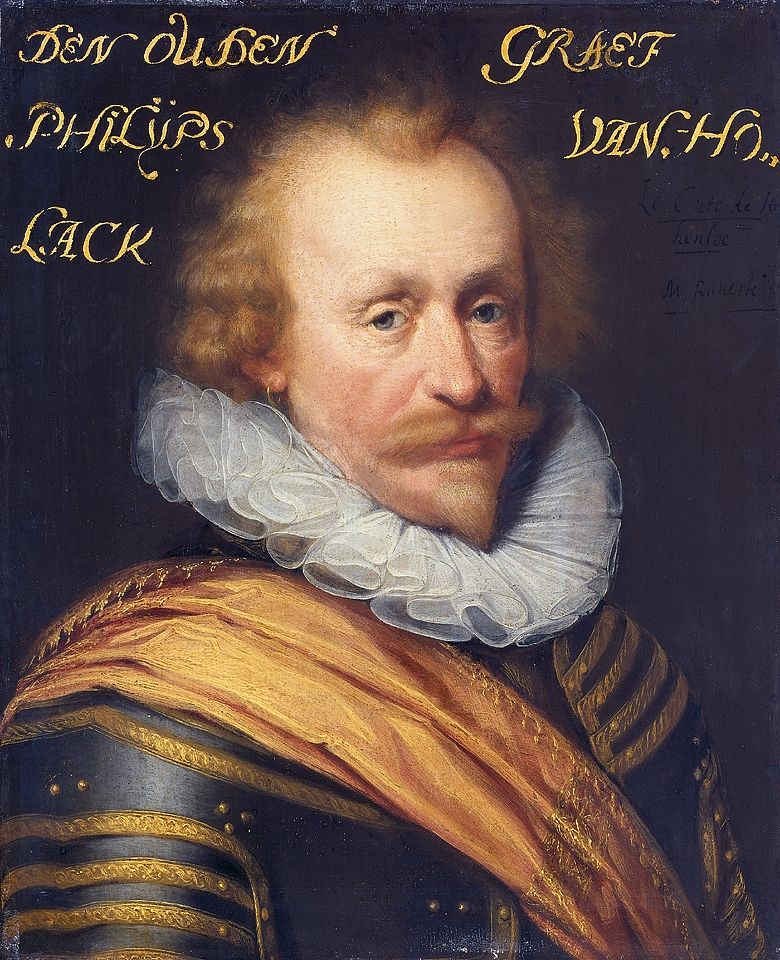

On 6 November 1583, under the command of Philip of Hohenlohe, about one thousand German soldiers sailed to Terneuzen, crammed into thirty small ships. The whole area had just fallen back into Spanish hands. However, Hohenlohe succeeds in thwarting the imminent loss of the strategically located Neuzen. His men erected the Moffenschans fort south of the town. All that remains of this fort is the name of a farmstead on Axelsestraat. The Spaniards probably established a fort at Triniteit as a countermeasure and so the history of the Spanish State Defence Lines came into being.

Philip of Hohenlohe, painting circa 1639-1633 (Rijksmuseum Amsterdam).

Contributions to this fascinating landmark network were made by the Spanish, the Dutch State and the French military forces, mainly during the period from the Eighty Years’ War to the War of the Spanish Succession (1701-1714). Leading structural engineers such as Simon Stevin and Menno van Coehoorn were involved in the development of fortified towns and defence lines in the area. During the French Batavian era (1794-1813/14), the Belgian Revolution (1830) and both World Wars, the defence lines still played a role and adjustments were made.

The fortified town of Hulst (Google Earth).

Fortified towns

The biggest fortified towns of the Defence Lines are in Belgium: Bruges, Ghent, and Antwerp. The most well-preserved fortified towns in Zeeuws-Vlaanderen are Hulst and Sluis. The village called Retranchement even owes its origin to the two forts Oranje and Nassau (1621/22). Elsewhere, new villages or hamlets arose out of the fortifications, such as Turkeye, Philippine and, in Belgium, Lillo on the righthand shore of the Schelde (part of Zeeland until 1786).

The ramparts of Sluis, seen from Westpoort (photo H.M.D. Dekker).

Even in Aardenburg, Sas van Gent and Philippine, many traces and reminders can still be found. After the conquest by Prince Maurits, three quarters of old Aardenburg (‘the old town’) was excluded from the new fortifications. Biervliet, too, lost a substantial part of its original size. Middelburg in Flanders, just across the border, became a Spanish opposing fort in Aardenburg.

Forts in defence lines

Individual forts often date back to the later 16th century. Afterwards, many of these were linked by the construction of defence lines with dikes and/or waterways. The Zandberg and De Rape forts east of Hulst, for example, were built by the Spaniards after the State had breached the dikes of Saeftinghe in 1584. Both forts subsequently became part of the (State) Defence Lines of Communication east of Hulst (1591).

The fortified towns and independent fortifications were eventually interconnected by more than twenty separate defence lines in the form of dikes and/or waterways. During the Eighty Years’ War, for instance, the (Spanish) Defence Lines of Communication between Hulst and Sas van Gent (1586-1634) and the Defence Line of Oostburg (1587-1604) were also established. During the time of the Franco-Dutch War (1672-1678), which started with the infamous Rampjaar (‘Year of Disaster’), the The Passageulel line came into being. During the Nine Years’ War (1688-1697), the price for the English regency of Prince William III, the Linie van de Oranjepolder near IJzendijke was created. Locks and other water structures also became part of the Spanish State Lines, such as the Stenen Beer in Zandberg near Hulst (1784).

The ‘berenning of Aardenburg’ by the French, 1672, anonymous work (Het Belfort, Sluis).

Public access

Apart from their potential for cultural tourism, the line segments also have ecological values and contribute to a regional identity that crosses borders. Historians, publicists and folklorists have long been aware of the great importance of the Spanish State Lines. Not only in terms of military history, but also when it comes to the history of taxation, inundations, religious struggles, occupation and oppression, and the creation of the national border. Even for intangible folklore. There are some wonderful tales associated with various sections of the line, such as Jantje van Sluis or the Rondute Treasure.

Stone watchtower of the Kruisdijkschans, drawing from 1692.

Around the turn of the last century, the government intervened. The Belgian provinces of East- and West Flanders, the Dutch province of Zeeland, the city of Antwerp and some 25 other partners took an integrated approach to making the Defence Lines more easily accessible. In 2006 and 2007, the restoration and refurbishment of several forts and defensive structures began. Such as (in the Netherlands) the Olieschans (Aardenburg), the Kruisdijkschans (Sluis/Aardenburg), Fort Berchem (Retranchement) and several forts near Koewacht (Sint-Jacob, Sint-Joseph and Sint-Livinus).

The ramparts of Hulst were provided with a wheelchair-accessible path. More than thirty information panels were installed throughout Zeeuws-Vlaanderen and bike and walking routes also followed the Defence Lines. In most cases, the redesigns and restorations were also linked to the further development of nature.

Current

Additional products were made, such as the comic book Suske en Wiske en de Laaiende Linies (Dirk Stallaert, 2011) and the informative publication for the general public. De Staats-Spaanse Linies. Monumenten van conflict en cultuur (Jan J.B. Kuipers, 2013). Other publications include a marketing study, an educational package, leaflets and brochures, information banners and beach flags. Symposiums and a fort night have also been organised. The latest developments on public access and acessiblity and activities can be found on the official website.