Drowned villages

Nowhere along the North Sea coast are there so many drowned villages and drowned stretches of land as in Zeeland. Floods and the loss of land and villages have been happening here for ages now.

As far back as Roman times, areas were already being lost. The once very prosperous Ganuenta now lies at the bottom of the Oosterschelde at Colijnsplaat, but it was an important transport port in those days. The goddess Nehalennia was worshipped here. Remains of a sanctuary dedicated to her were found in the Oosterschelde. This was reconstructed in 2005 near the port of Colijnsplaat and is open to the public free of charge.

Drowned church villages

There are about 200 drowned villages in Zeeland. The majority were lost in the late Middle Ages (between 1000 and 1500 AD – there were more than 45 storm surges between 1134 and 1530 alone). This high number is probably due to the specific geography of Zeeland. It is an area with wide river mouths and strong tidal forces. This location offers economic opportunities, but the downside is its considerable vulnerability. People also caused floods themselves: dykes were neglected and damaged by salt and peat extraction or areas were flooded for military reasons.

Location of the drowned Tolsende in the Oosterschelde (Erfgoed Zeeland).

Swallowed up by the waves

Particularly from the twelfth century onwards, many places in Zeeland were swallowed up by the waves. The large expansion of reclaimed land in those days meant that the water had less room and sought a way out. And that caused dykes to break, the land to flood, people to perish and many people to lose their homes and possessions. As it happens, lost land was often dammed up again, so that many drowned villages now lie inside the dikes once more. Villages were also regularly rebuilt further away at a safer location.

Monument to the Drowned Villages

In remembrance of the drowned villages, the Monument for the Drowned Villages is located on the Oosterscheldedijk just east of Colijnsplaat. It was designed by the Amsterdam artist Lydia Schouten and serves as a reminder of the church villages that have disappeared due to flooding. Every day at 11.34 am, 2.04 pm and 3.30 pm (the times refer to the years of the major floods), a sound composition can be heard here. On the steps leading to the water, you can read the names of drowned villages and a few, always relevant, lines of poetry in response to the Sint-Elisabeth flood: ‘Het geldt voor nu, het geldt voor later. Wantrouw de macht van wind en water.’ (‘It is true for now, it is true for later. Distrust the power of wind and water’.)

Reimerswaal

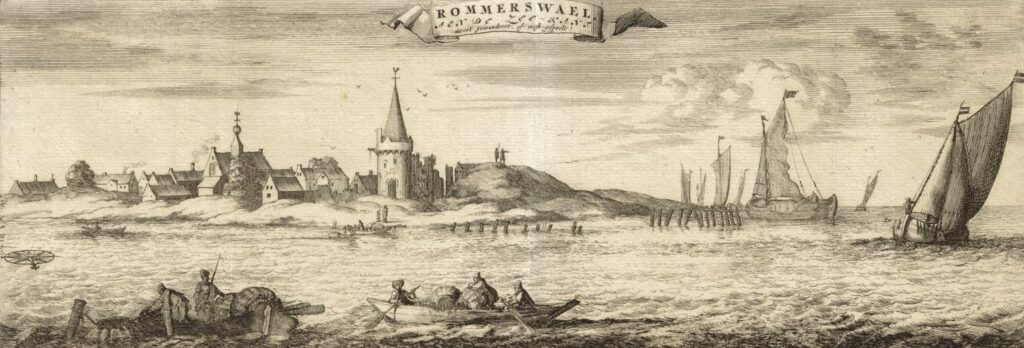

Reimerswaal is one of the best known drowned places in Zeeland. It was once the third largest town in the province and is said to have had around six thousand residents. The last century for Reimerswaal was an ordeal of floods and town fires. The town was severely battered by floods in 1532, 1552, 1555 and 1557. Another storm and a town fire came on top of that, followed by a whole series of storm surges. The Eighty Years’ War did not leave the city unscathed either… In 1631, the last couple of poor mussel fishermen left the town and, three years later, the remnants of the once so proud Reimerswaal were sold by public auction. Initially Reimerswaal was still recognisable as an island, but it finally sank in the Oosterschelde in the nineteenth century.

The town of Reimerswaal, as it once was, in the 1696 publication Nieuwe Cronyk van Zeeland by the historian Smalleganges (Zeeuws Archief, KZGW, Zelandia Illustrata).

Archaeology in the Drowned Land of Zuid-Beveland

Not much can be seen of Reimerswaal anymore. Part of it lies at the bottom of the Oosterschelde: another part lies under the Oesterdam. But when it’s low tide, you can enjoy a magnificent view of a vast area of mud flats from the Rattekaai tide port. This is the Drowned Land of Zuid-Beveland where, apart from Reimerswaal, quite a few villages have been lost. Nieuwlande is the best known of these, because it was relatively easy to reach. This is why many findings have been made here. Some of them can be viewed in the Oosterschelde Museum in Yerseke.

There is an information point about the history of drowned villages in Zeeland at the Bergse Diepsluis on the Oesterdam, the location where Reimerswaal once flourished.

Valkenisse

Valkenisse drowned in 1682. It lies on the mud flats in front of the salt marshes of Waarde, on the northern side of the Westerschelde. The village is legally protected as an archaeological monument, but – and this is what makes it so unique – is also physically protected by breakwaters. It used to be an entire ring village, which even had a modest brick castle with two towers. A huge amount of archaeological research has been carried out here. This has taught us, for example, that the castle’s residents led a relatively simple life. Remnants of commonly-used pottery and food were found in their cesspits, but occasionally the castle dwellers would indulge in feasting on poultry such as peacocks and swans. Remains of these have also been found.

Koudekerke and the southern outskirts of Schouwen

Between 1475 and 1650, a large strip of polder land (sometimes as wide as four kilometres – altogether around 3,500 hectares) was lost on the southern outskirts of Schouwen. This led to the loss of at least fifteen villages. Now there is a deep fairway section of the Oosterschelde estuary. The only remnant of the area is the monumental church tower of Koudekerke, Koudekerke, the Plompe Toren, which sticks out high above the landscape.

The mermaid of Westenschouwen

Today, the tower of Koudekerke is a Natuurmonumenten visitor centre where you can learn all about the saga of the mermaid of Westenschouwen. The inhabitants of this village are said to have let a mermaid die on purpose. The merman who was then left alone cursed the village:

‘Schouwen, Schouwen,

’t sal je rouwen

dat je genomen eit m’n vrouwe!

’t Rieke Schouwen zal vergaen,

alleen de toren zal bluven staen!’ (Schouwen, Schouwen, It will bring you grief That you have taken my wife! All of Schouwen will perish, only the tower will be left standing!)

Strictly speaking Westenschouwen is not a drowned village. The harbour became silted up and the rich fishermen were forced into begging. The tower of Westenschouwen did not stand the test of time either, but was demolished in the nineteenth century. According to folklore, the mermaid now lives in the Plompe Toren of Koudekerke. The remains of the port of Westenschouwen can still be seen at low tide on the beach of Westenschouwen (Rotonde beach crossing).

Blasphemous lead pewter brooch, with the image of a merman, found in Westenschouwen, dated 1400-1450 (Gemeentelijke Musea Zierikzee).

Research

The drowned villages captured the imagination of people early on in history. One of the first to concern himself with them was the regent and chronicler Jacobus Ermerins, who in the eighteenth century was astonished at the fact that the once so great Reimerswaal had fallen into oblivion. Ermerins sailed on a flat-bottomed boat from Tholen to the drowned town. There, he wandered over the mud flats and found the foundations of houses, town walls and towers, and the spot where the church had once stood.

Piet Zuijdweg

Countless researchers followed in the footsteps of Ermerins. The Drowned Land of Zuid-Beveland was at one time so popular that dozens of archaeological day-trippers could be encountered there. But there was also a lot of valuable and ground-breaking pioneering work being done in the province. Piet Zuijdweg mapped out many of the remains of drowned villages in Noord-Beveland. For instance, he researched the vanished village of Emelisse. Four sarcophagi were found, as well as a sandstone head that was probably once part of a pillar. It may represent St John the Baptist, but also the mythical ‘green man’ who is very famous in England. You can admire this statue in the Historisch Museum de Bevelanden.

Hannekenswerve

Jan van Hinte was very actively involved in Zeelandic Flanders. For example, he led the excavation of the church of the vanished village of Hannekenswerve and mapped out the accompanying graves and crypts. A number of the gravestones found there were moved to the Sint-Baafskerk (Saint Bavo Church) in Aardenburg and one can be seen in the Gemeentelijk Archeologisch Museum Aardenburg, the municipal archaeological museum of Aardenburg.

Overview of the excavation of Hannekenswerve by Van Hinte, 1964 (ZB, Beeldbank Zeeland, photo T. Kannegieter).

1953 and beyond

The last great flood happened in 1953. After that disaster, a few villages on Schouwen-Duiveland were abandoned for good. Due to climate change and rising sea levels, the subject of drowned villages remains topical, now and in the future. Would you like to know more about how water will be managed in the future? Then be sure to visit the Watersnoodmuseum. There, they not only look back on the 1953 disaster, but also take an in-depth look into the future.