The Zeeland ‘beiaard’

by Janno den EngelsmanThe art of ‘beiaard’ playing is a musical tradition that originates from the Low Countries. A ‘beiaardier’ plays the beiaard, which is suspended high in the tower of a historic building near a street or square where people gather. During the weekly market days and on public holidays, the ‘stadsbeiaardier’ (town carillonneur) will give a music concert of bells. Beiaard music is as such a resonant presence in the historic townscape. The beiaardier creates atmosphere in the town and his music unites residents and visitors.

Carillons can be heard in many places in Zeeland. Carillons that are played by beiaardiers are located in Middelburg, Vlissingen, Veere, Goes, Tholen, Sint-Maartensdijk, Zierikzee, Axel, Hulst and Sluis. Furthermore, grace notes are rung in various places in Zeeland. These are rung automatically. It is remarkable that two of these grace notes are among the oldest in the world, namely in Zierikzee (Zuidhavenpoort) and Arnemuiden, with the bells dating from the mid-sixteenth century.

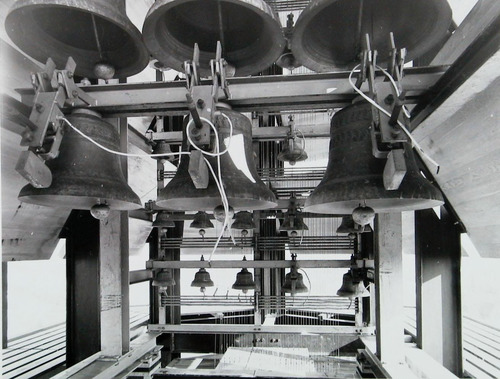

Carillon in Vlissingen, circa 1968 (ZB, Image Bank Zeeland, photo A. van Wyngen).

History of the beiaard

The beiaard, also called a carillon or ‘klokkenspel’ in Dutch, has its origin in the Low Countries around 1500. By the end of the fourteenth century, Vlissingen and Middelburg were already the first towns in Zeeland where the predecessor of the beiaard introduced extra notes into the church and town hall towers, known as the ‘voorslag’, as in grace notes. Bells in the clockwork played a short melody just before the hour to herald the striking of the hour. This was done using a ‘speeltrommel’ (carillon). From 1500 onwards, it became possible to play the carillon manually by using a baton clavier. Ever since, carillonneurs play ‘live music’ with the baton clavier. The automated chimes ring daily on the hour and on each quarter, as part of the time-keeping service.

The beiaardklavier, a carrillion keyboard, with a manual or baton clavier and a pedal or foot clavier (photo Janno den Engelsman). This clavier is in the Lange Jan in Middelburg.

The bells for the carillon were made in foundries. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Amsterdam and Antwerp were important centres for bell foundries. In Middelburg, between 1600 and 1679, the Burgerhuys family was active as ‘the country’s artillery- and bell-founders’. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, there was less of an interest in beiaard culture, but a revival sprang up around 1880, partly due to the efforts of the Flemish beiaardier Jef Denijn.

During the Second World War, many of the bells were taken out of the towers by the Germans to be used in the war industry. The carillons of Tholen and Zierikzee and many loud bells from several towers were unable to escape the German plunder of bells. When these beiaarden were transported by ship across the IJsselmeer towards Germany, people deliberately sunk the ship. After the war, the ship was lifted out of the water and the carillons were returned to the municipalities. A number of carillons from Zeeland were also lost during the war. During the reconstruction, several new carillons were made and placed in the restored town towers. Vlissingen, Middelburg, Hulst and Sluis all received new instruments as a result.

Playing the carillon

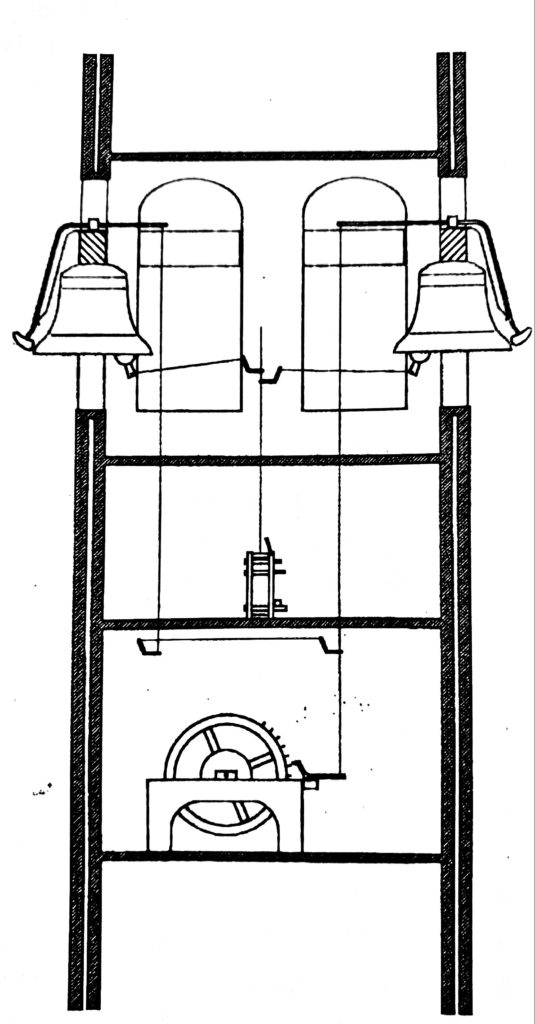

The carillon clavier is made up of a manual or baton keyboard and a pedal or foot clavier. Each key of the manual or pedal is connected to a clapper via a metal wire. The beiaardier strikes the keys with the pinky finger with loosely-clenched fists or, if they want to press two keys at the same time, with their thumb and fingers. This causes the clapper to strike the inside of the bell, which in turn makes it chime. The tempo and the way the key is moved determine the dynamics and the musicality. The beiaardier can, with two hands and two feet, make the bells ring at the same time.

Schematic representation of the workings of a beiaard (private collection Janno den Engelsman).

Thanks to the automated working of the carillon, the beiaardier does not have to climb up every half hour or quarter hour. The position of the metal peg on the playing drum determines the melody, the pegs operate a hammer which strike the bell so that it rings. Several times a year, the musical composition has to be replaced by new music. The town carillonneur sometimes spends two or three days in the tower adjusting the metal pegs so that the new music can be played. Nowadays, the carillonneur can also program the music for the automated timekeeping system on a computer.

Beiaardiers

Without beiaardiers, both qualified and amateurs, there would be no beiaard music. Many beiaardiers have received professional training from the Netherlands Beiaard School in Amersfoort or the Royal Beiaard School in Mechelen. The above-mentioned carillons in Zeeland each have their own town carillonneur. Thanks to the incorporation of contemporary music in the repertoire of the town carillonneur, this musical heritage is kept ‘in tune with the times.’

Beiaard culture has been placed on the national list of intangible cultural heritage, which stemmed from the signing of the UNESCO Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage by The Netherlands.